MY NAVY MEMORIES

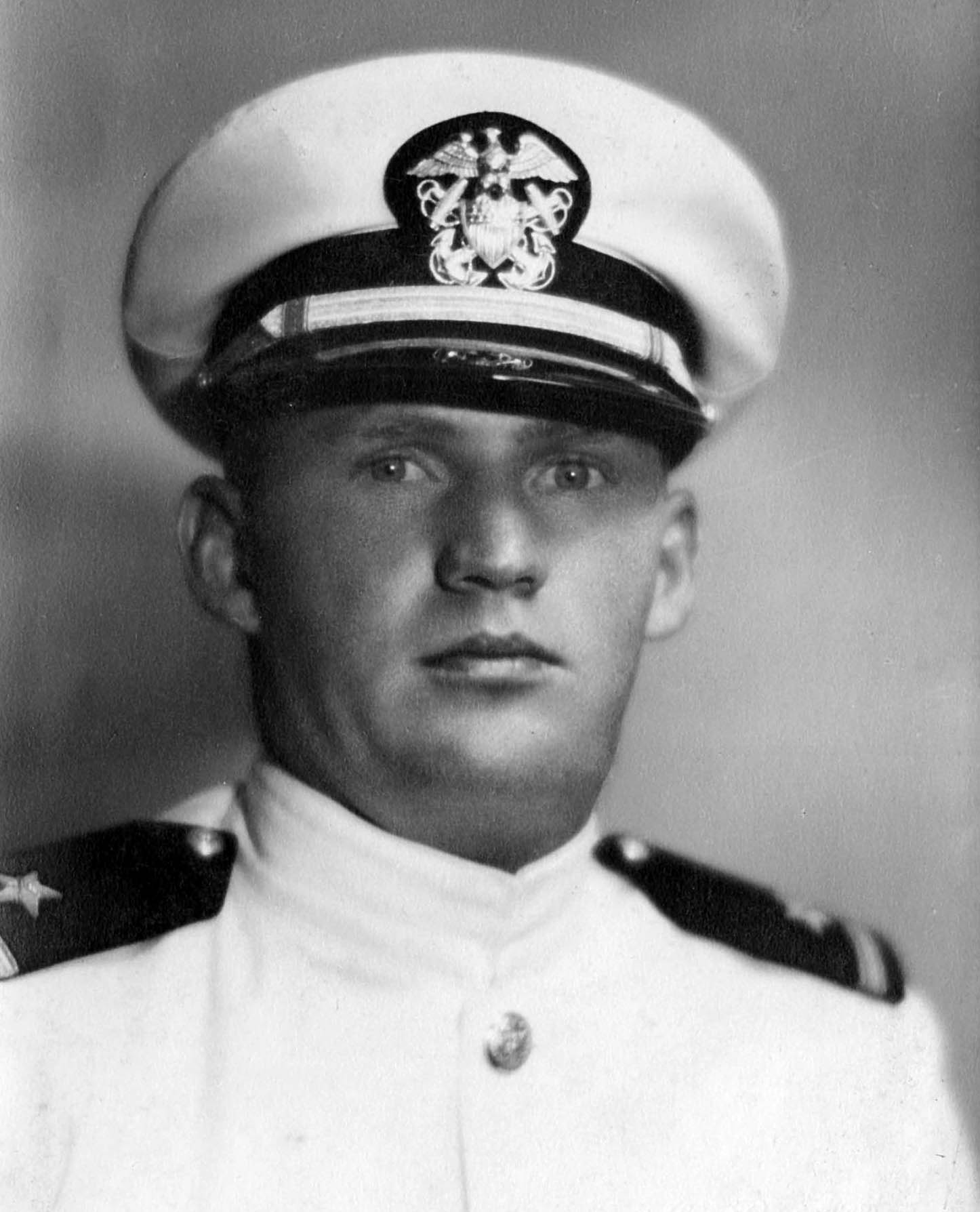

George S.K. Rider

Ships That Pass In The Day, 1956

This is George Rider’s account of a memorable day when Abbot refueled at sea. See also George’s stories about the Saint Patrick’s eve tragedy and Abbot’s brush with catastrophe.

At sea aboard the U.S.S. Abbot, late summer of 1956, we were steaming in formation with the carrier Antietam, several replenishment ships, twelve destroyers and four destroyer escorts, all involved in a Hunter-Killer (HUK) exercise. Our task was to protect the supply ships from four prowling submarines and at the same time act as a screen for the Antietam’s flight operations, in support of the anti-submarine warfare mission (ASW). We were operating in the south Atlantic.

Ominous rumblings in the Middle East portended an uncertain future. Nasser was sword rattling in Egypt. The exercises took on added significance. Three months later, we would find ourselves patrolling in the eastern Mediterranean. Nasser had sealed off the Suez Canal, blowing up several ships and completely blocking traffic.

I had turned 24 on May 16th and was soon to be promoted from ensign to lieutenant (junior grade), a product of Yale ROTC, 1955.

At breakfast a week into the exercise, our captain — Commander W.W. DeVenter (we referred to him as WWD), a much decorated Annapolis graduate, announced in the ward room, “Red, report to the bridge at noon. You’re going to take us alongside the Antietam to fuel.”

My heart started to pound. I was the youngest of three ensigns, two Annapolis grads and me, proud to be the first of us chosen. I was anxious in more than one way. Fueling at sea is an exact procedure, a tricky evolution demanding timing, discipline and teamwork. From the time the first line is received until you disengage, chances for dangerous errors are ever present.

Thoughts of Dad and my grandfather flashed before me. Dad was British. During World War I at the age of 17, he was serving as a radioman on a minesweeper. His ship was torpedoed and sunk. The torpedo struck amid ship, the boilers exploded and his ship went down in minutes. The German U-boat surfaced and machine-gunned the survivors in the water. Only a handfull of the crew survived, clinging to floating debris. Most never had a chance. Dad was creased in the scalp and right knee, one of the lucky few. The ship’s carpenter, floating close to Dad, plucked their brown and black spaniel, “Scotty,” from the water and placed him safely on a floating hatch cover before he slipped beneath the surface for the last time.

I thought of my grandfather whose eyesight was so bad he was turned down by Annapolis and the regular Navy. The sea was in our blood. How proud Dad and Gramp would be to know of my pending assignment.

In 1955, my brother Ken was a senior at Brown — also enrolled in the NROTC. That December, the Abbot was in dry dock in the Charlestown Navy Ship Yard in Boston for refitting and undergoing overhaul.

Ken was a key player on the Brown hockey team. One January night I invited WWD and my boss Ed Kline, the gunnery officer, to watch the game between Brown and Northeastern in the Boston Garden. Ken scored an early goal and for his efforts was crosschecked in the head on the next shift, breaking his nose and spilling blood all over center ice.

They set his nose, and he returned late in the 3rd period wearing an improvised facemask. Ken extracted a measure of revenge. With the ref skating up ice, watching the puck, he turned back behind the ref and cold cocked the enemy nose-breaker. Brown won. After the game, Ken joined the three of us at a bar in North Station sporting two black eyes, ten stitches and a bandage that periodically oozed blood drops on the table. He was an instant hit with WWD and Ed. After a quick visit and two beers, he left to join his team for the bus ride back to Provincetown.

The next day, WWD asked me what I thought about Kenny joining us for duty on the Abbot. I was ecstatic. We were very close. The wheels were put in motion. Ken was thrilled and fired off his requests to the Brown Professor of Naval Science, a captain. The PNS notified BUPERS, the Bureau of Navy Personnel, in Washington. Because of the tragic loss of a light cruiser in World War II taking the lives of five Sullivan brothers, the Navy mandated parental consent in writing for family members to serve together on the same ship. Mom was reluctant at first, but agreed at the urging of Ken, Dad and me. WWD also forwarded a letter of request.

Ken came aboard in early July 1956. He joined us in Norfolk on a stopover in route to our ASW exercise in the South Atlantic. At that time, we were the only brother combination serving together as officers on the same ship in the entire U.S. Navy. Mother later received a letter from Mamie Eisenhower acknowledging our service together.

I reported to the bridge early for my assignment, checked our course, speed and bearing to the Antietam. I was keyed up like a rookie hockey player in his first shift waiting for the puck to drop.

We were steaming ahead of the carrier, off to starboard, as part of an eight-destroyer screen. One of the other destroyers had just finished fueling and was in route back to the screen as a second destroyer maneuvered into place. It was time for us “to get in line” at the pump.

“Right full rudder, make turns for 15 knots, come to course 140 degrees,” I stammered. The butterflies exited. We circled back and around astern to starboard of the Antietam, assuming a parallel course and speed and in line with the destroyer fueling ahead of us.

Our turn came. I gave orders to increase speed, and we settled into place alongside the Antietam, adjusting course, speed and spacing. Our deck force was outstanding, led by Boatswain Mates First Class J.J. Cunningham and Shoemaker. Receiving and connecting the fuel hose and the high-line for exchanging mail, films and personnel and occasional goodies like fresh ice cream were routines they handled with skill and enthusiasm. Fuel was flowing and the high-line transfers were taking place at a fast pace. The sea state was moderate.

I was so preoccupied with our positioning, fueling and transfers taking place, that I failed to notice the activity on the carrier’s bridge, several stories above us. To my astonishment, their OOD hollered down through his bullhorn, “George Rider.” I looked up to see John Cochrane our Brightwaters, Long Island, neighbor waving down. My cap was off. The red hair helped the identification. John was several years older, an Annapolis graduate and a role model to many of us facing military service. Dad and Gramp followed his career.

I called to the Petty Officer of the watch, “Get my brother up here.” He was standing watch in CIC (Communication Information Center), a space crackling with speakers, crowded with radar scopes, chart tables, plot boards and the men to operate them, the nerve center of the ship.

Kenny appeared. We hollered and waved up to John, caps off. Kenny also had red hair. John’s captain shouted at him, “What’s going on down there on that destroyer?”

“Those redheads are brothers. They’re friends of mine from my hometown. They are a little nuts.”

We topped off and began to disengage. The Antietam’s band serenaded us from the flight deck. The last two numbers played were The “Navy Hymn” and “Anchors Away.” The memory still gives me goose bumps. I ordered course and speed changes to take us back to our position in the screen. And received a “well done” from our captain, WWD, who never moved from his chair on the bridge. The carrier graded us on the fueling exercise. We received top marks, no doubt with an assist from John.

At the conclusion of the operation we proceeded to the Mayport Naval Station in Jacksonville, Florida. The Antietam was already in port. Ken and I wasted no time in looking up Lt. John, who immediately suggested a debriefing at the officers club. The Ensigns Rider were treated to several “adult” beverages and the company of our hometown friend.

What a great memory, Ken and John witnessing my first major assignment. Ken died in 1995. We shared so much together. Both John and I married and settled in our hometown, and raised our families. My wife Dorothy and John and his wife Betty see a lot of each other.

When our cars pass in town or our boats pass on the bay, I think about Ken and John and that day in the South Atlantic fifty years ago. Then I smile and tip my cap.

— George S.K. Rider