MY NAVY MEMORIES

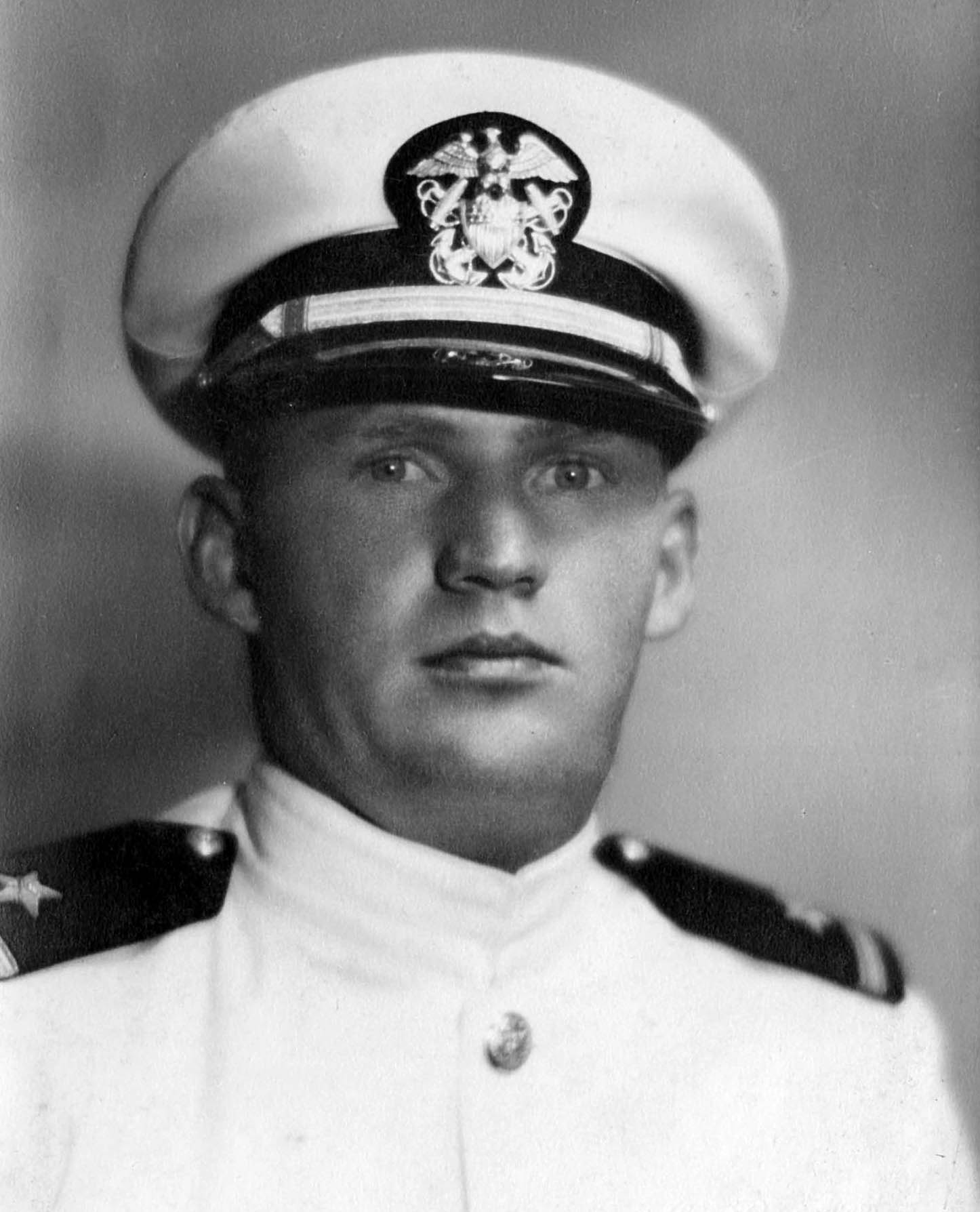

George S.K. Rider

Saint Patrick’s Eve Tragedy 1956

George Rider transfered to Abbot from the Fletcher-class destroyer Preston at the Charlestown Yard in Boston in December 1955, shortly before Preston sailed for the Pacific. His brother Ken reported aboard Abbot in June 1956. They are believed to be the only brothers who served together as officers during that time.

This is Georges’s account of the day four destroyermen died, and how he decided to stay aboard Abbot. See also George’s stories about Abbot’s brush with catastrophe and a memorable refueling operation.

St. Patrick’s Day has come to be known for parades, parties and celebrations. For four brave Navy men in Newport, R. I., this day was just the opposite.

In October 2008, my daughter Jenny and I were attending an alumni meeting at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. After dinner she arrived at my table with a young man in tow.

“Dad, meet Harry Flynn. I think you were in the Navy with his dad.”

Indeed, I was. We were roommates aboard the USS Preston. I had not spoken to Harry Sr. in 52 years. The next day, between meetings, Harry called his father and handed me the phone. The years vanished as we caught up. What a warm feeling watching our kids talking as we spoke.

As a result of that chance encounter, we began to email and talk. We both enjoy writing and started swapping some of our stories. One of his, “Safe Harbor — Not,” dealt with the events of St. Patrick’s Eve 1956.

Several months earlier, another chance encounter occurred at the 19th Hole Bar, in my hometown of Brightwaters, Long Island. Several of us served on destroyers or destroyer escorts, stationed in Newport during the mid-’50s, and we were reliving the experiences with Doc Pettit who was also home ported in Newport at the same time. Doc was a Medical Corpsman aboard the destroyer tender Cascade. He later became a highly respected doctor in our community, specializing in family medicine.

Like Harry, Doc Pettit would supply a first-hand account of the events that night and the next day.

Their stories triggered a wave of memories. I couldn’t get the details and events out of my mind.

I dug further. The Newport Library sent me the front-page article that appeared in the Newport Daily News on Saturday, March 17, 1956, describing the St. Patrick’s Eve storm that lashed Newport, as “a blizzard, howling with 70-mile-an-hour winds and a snowfall of ten inches that created drifts that reached as high as five feet.”

Harry had transferred from the Preston to the Irwin to serve on the staff of the Commodore who was in charge of Destroyer Squadron 24 (DesRon 24). Both the Preston and the Irwin were part of Destroyer Division 241. (Four Destroyers make up one division, and two divisions constitute a squadron.)

As Harry recounted, “I had the staff watch that day, and a lot of people had already left the ship on liberty or shore leave. We were in a nest of four Fletcher-class destroyers, 2,100 tons each of sea-going greyhounds. I was waiting for my fiancée and her cousin to come out to the ship for supper, and then go back on the launch and drive back to Boston where they were living.”

The Preston had just returned to Newport from the Charlestown Navy Shipyard in Boston where she had undergone her scheduled yard overhaul. They went in before Christmas and got out in February. The Irwin had undergone overhaul in the yard in Philadelphia.

Harry noted, “We had only just arrived back in Newport within days of St. Patrick’s Day. A ship just out of its shipyard tour is always in a state of flux, with a lot of new people and old hands who should know better getting familiar with the ship and their duties all over again. Ordinarily everyone works hard to get in shape and somehow the nation survives. But this time everything worked against us.”

“We knew a storm was coming, but storms in Newport in February are not exactly headline news. Besides, none of us in DesDiv 241 of DesRon 24 joined the Navy expecting the seas to remain calm and the weather balmy while we completed our hitch. On the first trip aboard my first Destroyer, the Preston, we were rounding Nantucket Light when the hatch above my bunk sprang open and water from the bow poured in, flooding our sleeping area. Talk about leaping out of the rack and heading topside, I realized I could get around that little ship a lot faster than I ever thought possible. So storms aren’t unusual, but never fun.”

Harry continues:

”We began sending the liberty launch in at four o’clock. The wind had come up and made the trip very rough. When the boat crew returned for another trip, the 40-foot launch was landing between the sterns of the Preston and the Irwin. I went to the commodore, my boss, and suggested he decide when to cease boating because it was really getting rough out there. He said, “Stop ’em after the next boat comes back,” and I went to the stern of the Irwin where the launch was tying up.

“Someone slipped or something happened and the crewman on the bow fell into the freezing water. There was much milling around. Several of us shouted to throw him a line from our ship. A rope for the purpose could not be found. Meanwhile the engine in the launch stopped running, so they couldn’t push it up into position where it could be secured. It began to drift aft.”

The Newport Daily News article filled in more details:

“The launch was tossed so high on the waves that its keel could be seen from the destroyer deck. As the launch neared the Preston, two of the boat crew jumped across to the Preston’s deck. When the bowman tried to follow, he slipped and fell into the water. Crewmen on the Preston scrambled down and grabbed him by the life jacket, but he was torn from their grasp when a strap broke. The launch drifted away.

“The Preston immediately ordered out their whaleboat (a 24-footer) to assist in the rescue. Five men boarded the boat, including Annapolis graduate, Lt. (jg) John Juergens and Reese B. Kingsmore. They found the 40-footer. The two got aboard and started the engine.”

“The three others stayed in the whaleboat and bravely continued to search for the sailor who had fallen overboard.”

Boatswain Mate 2nd Class R.C. Moore served as coxswain, although that was not his normal duty. According to the Newport Daily News, before they left the Preston, he told his shipmates he was going along, “To make sure everything is done right.”

Harry’s account picks up the story:

“It was with great excitement we saw the liberty launch appear out of the storm and steer into the nest between the two destroyers where it had been parked originally. The crew and their hero ensign were taken below for warm, dry clothing and medicinal brandy.

“The wind had come up with a wild ferocity, and the heavy snowfall limited vision to a few feet from the nest.

“I reported back to the commodore, who wanted me to stay on the situation and report back to him. I stayed in the wardroom for some time, with an ensign I didn’t know too well and his girlfriend, who had come out to visit and didn’t make the last launch to the landing. There were no such things as cell phones in those days so I had no way of knowing how my fiancée and her cousin were doing, although I heard later that they stayed all night, waiting to find out what had happened.

“The storm was wicked and we were constantly worrying about the nest of four destroyers breaking up or drifting. The four ships of DesDiv 241 rode out the storm, but there were casualties…”

During all of these dramatic events, I was home at my parents’ house on Long Island enjoying a rare 72-hour pass from my new ship, the USS Abbot.

“George! George! Wake up. Deanie Gilmore just called to see if you are all right.” Mother was standing next to my bed.

“There’s been a terrible accident aboard your old ship. She’s checking to see if you are all right.”

I woke from a sound sleep trying to make sense of what I was hearing. I had transferred from the USS Preston in December 1955. Both the Abbot and the Preston had been undergoing updates and repairs at the Charlestown Navy Ship Yard in Boston. The Preston and the three other ships in her Division were scheduled to join the 7th Fleet for assignment in the Pacific. The Abbot was part of the 6th Fleet and would remain in the Atlantic operating out of Newport.

Swaps between ships leaving for the Pacific and those remaining on the East Coast were approved if an individual could find a counterpart with the same job on the other ship and the COs of both ships agreed. I opted to stay on the East Coast and found my replacement on the Abbot.

The Preston had not yet departed for San Diego. Their division was undergoing refresher training.

Dean Gilmore was the daughter of friends of my parents. She had turned on the radio early not knowing that I had transferred, and heard the story of the accident.

I knew instinctively that some of the men in my division had to be involved. I spent most of the morning trying to contact the base for more information. The Abbot was due to get underway from Boston early that Monday. The weather was God-awful. I couldn’t take the chance of getting stuck in Newport and decided against my first impulse, which was to go there immediately. I sent a telegram to the captain of the Preston offering my prayers and any help I could be, still not knowing the details of the tragedy.

As the day progressed, the story unfolded. Sketchy details began to emerge on the radio and TV. I finally got through to the office of the Base Commander. The duty officer delivered the worst possible news. Not only had the sailor who had fallen overboard from the launch died, the three who had selflessly set out to rescue him in the whaleboat had also perished. No names were released pending notification of next of kin.

Sometime in the early afternoon, the names of the sailors were released. I tuned in to the news on the radio. My heart sank as the commentator read the names:

Boatswain’s Mate 2nd Class Robert C. Moore of Marked Tree, Arkansas; Seaman Donald Britton of Bayville, N.J.; and Seaman Gary C. Hutchinson of Holland, Ohio. All were from the Preston. Kenneth R. Kane (the bowman originally swept off the launch) of New York City, a fireman in the crew of the Irwin.

I had been the Division Officer for the three men from the Preston.

I knew R.C. Moore the best. He was a rangy, easy-going southerner, with a great sense of humor. He took his responsibilities to heart. He was popular with officers and crew alike. He took me under his wing when I reported aboard, as a young inexperienced ensign. Thank goodness!

Britton and Hutchison were two squared-away seamen serving in the deck force, too young to have fulfilled their full promise. The deck force is the training ground from which other activities aboard draw their personnel. They were both headed for greater responsibilities. The deck force was my responsibility.

One of my collateral duties was ship’s athletic officer. We entered the base “touch” football league. R.C. was no stranger to the game. He starred at end and halfback, while I labored as a lineman on both sides of the ball. The word “touch” appears in quotes for a reason. The games invariably turned into tackle without pads. We would usually repair to a bar on Thames Street to celebrate or lick our wounds. Our captain, Commander Peterson, was every sailor’s dream of a skipper and welcomed our efforts on the field. We were a very happy ship. He loved the competition.

I slumped into a kitchen chair at my parents’ house, images of the three men replaying in my mind. I struggled to process what had happened. Looking back, I recognize that moment as one of the turning points of my life, from young man to tempered adult. The weight of the loss, the sudden randomness of death, slowly sank in. So did the meaning of serving one’s country — of literally being willing to sacrifice your life for another’s.

But what I experienced was nothing compared to Doc Pettit, as he shared his experience with me at the bar of our country club 50-plus years later. His voice was filled with emotion even after all those years.

Like the destroyers of DesDiv 241, Doc’s ship, the tender Cascade, was moored in the harbor nested with several destroyers.

Doc recounted, “As dawn broke on St. Patrick’s Day, the three man crew of the Cascade’s whaleboat and I got underway. We were moored with several destroyers out in the harbor and began to search for the missing whaleboat and its crew from the Preston. One of our crew spotted the boat, washed ashore on the beach of the Barclay Douglas Estate on Ocean Drive near the mouth of the harbor.

“As we approached, we discovered the frozen bodies of Moore, Britton and Hutchinson lying in the boat, their cherry-red faces contorted in death. They had died from exposure.”

As Doc punctuated his description with the words “cherry-red,” the emotion in his voice was evident. The image of those men in the boat would stay with him forever.

Harry recalled that six weeks later the four destroyers transited the Panama Canal and were steaming into the Naval Station at Long Beach, California. The temperature that morning was eighty-three degrees. Each ship carried a compliment of around two hundred and fifty naval personnel, all of whom were delighted to have left the Atlantic Fleet behind them.

Says Harry: “For me, my first view of Southern California was an absolute joy after the trauma of the storm in Newport Harbor. I decided then and there that I was where I belonged. Fifty years later, I’m still here.

“Thank you, Uncle Sam!”

Gone for a long time are those four brave sailors. The events of that tragic night in Newport and the sad morning that followed came easily back with the memories of Doc and Harry. Some might call it a coincidence that the three of us, more than 50 years later, would connect and reconstruct this tale. I think it’s more than that. Some stories buried in history simply demand to be told — and retold. This St. Patrick’s Day, along with your usual holiday festivities, take a moment to remember and celebrate the lives and heroics of these four fine sailors.

— George S.K. Rider

PS: The miraculous circumstances surrounding the recent successful ditching of U.S. Air Flight 1549 and the skill of pilot Chesley Sullenburger, his crew, the captains and crews of the rescue flotilla and the EMTs prevented the tragedy that surely would have occurred if the landing had not been so perfect, and the passengers had been forced into the water for any length of time. They would have suffered the same fate as those four sailors. They too would have died from exposure.