CHAPTER ONE

LAUNCHING, COMMISSIONING AND SHAKEDOWN

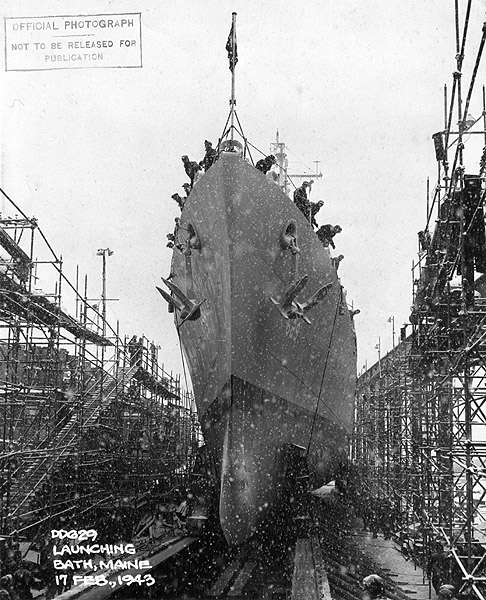

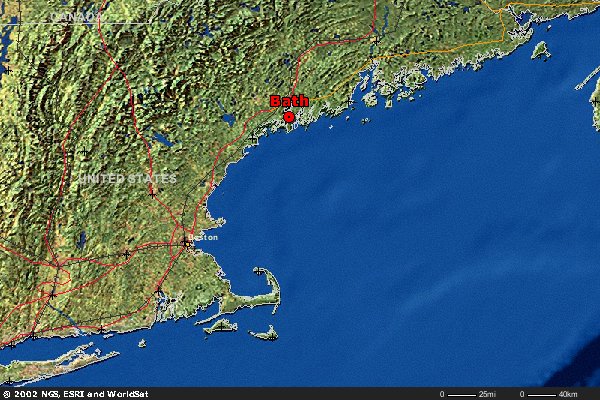

Snow was drifting down and the cold Maine wind was chilling the hundreds of shivering spectators and yard workmen that lined the Bath Iron Works’ ways or stood on the Kennebec River bridge to watch the launching of another destroyer for the mushrooming U.S. Fleet. A band played martial airs, speeches were shouted from a flag-bedecked platform and then Grace Abbot Fletcher stepped forward and slammed a ribbon-clad bottle against the knife-like bow of the ship that was named for her great grandfather, Commander Joel Abbot, U. S. Navy. It was then that the sleek hull slipped onto the Kennebec River. The Abbot had come to life. It was February 17, 1943.

Many were called to form the crew of the Abbot, but few were chosen to start building her from the keel up. Those who were fortunate enough to go to Bath followed a routine that any sea-going gob would envy. Reveille was at 0600, chow at 0630 and call to duty at the yard coming somewhere between 0830 and 0930. Yes, life at this “one barracks” Receiving Station was pretty enjoyable.

The most unfortunate thing that could befall one at this little sailor’s haven was a BIW watch which lasted from 1600 until 0800 the following morning. This watch was stood with loaded rifle and fixed bayonet, helmet and leggings, ready for any emergency that may arise. “Blackie’s” and “Mary’s Lunch” were a big help during those trying nights. A cup of “Jo” and a little talk with Shirley would make them pass much faster and much more pleasantly. If one didn’t have connections “on the outside,” it was a sound practice to bring liberty blues to the outfitting office at noon-time so that it wouldn’t be necessary to return to the Receiving Station and thereby miss the chance of getting in the line at the liquor store for your daily ration of spirits before the doors closed at 1700.

In the evening you’d take a little stroll to the USO for a few whirls and twirls with the city’s leading jitterbugs and then a wink of the eye, an elbow hook sent you off for the “Lobster Grill,” remembered by the Abboteers as the “Iron Fist (or Claw)” for a cup or two of “coffee” and a few cokes. Many a happy evening was begun in this way and the memory of this rendezvous will undoubtedly remain with the “Veterans of Bath” for a long time to come.

A ship’s party on the 21st of April was a forecast to the hospitable populace of Bath of the Abbot’s departure and it was with a moist eye and dry throat that it watched the “629” round the bend of the Kennebec River on the morning of the 23rd and slip out of sight…maybe forever.

A little over two months after the Abbot’s hull was launched, ordnance and other equipment had been added and routine tests had pronounced her ready for commissioning in Boston. Of the fifteen officers and forty-two men that were aboard her the day she left Bath for Boston only a few are still aboard: Lieut. Melby, Lieut. (jg) Koster, Gunner Auten, CMM Booty, CMM Montijo, CQM Hould, CWT Eads, CRM Bates, CMM McDonald, Johnston, EM1c; Loranger, Y1c; Kovach, MM1c; Nako, MM1c; Paulsen, MM1c; Wilson, MM2c; Nault, RdM3c; Walters, WT1c; Woosley, SM1c; Pradovich, GM3c; Eames, WT1c; Richard, EM2c; Lincoln, SM2c; Eldred, GM2c and Welton, MM2c.

On the 23rd of April at about ten o’clock in the morning the crew, which had been assembling for several weeks at the Fargo Building, was rushed in dress blues and with gear rolled in sea-going fashion to the Frazier Barracks in the Charlestown Navy Yard to wait three long hours for the Abbot to make her appearance. Finally she was reported standing in. What a ship! No sooner had she tied up than all hands were over the gangway. Shortly afterward the “old salts” that had brought her down from Bath got the “boots” squared away.

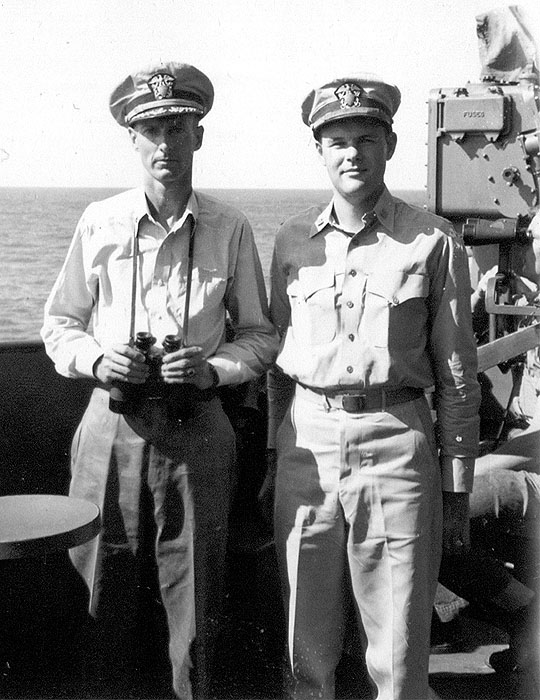

In the early afternoon, Captain H. C. Grady, USN, acting for the Captain of the Navy Yard and with the authority of the Chief of Naval Operations, officially accepted the Abbot for the U. S. Navy and the commission pennant was hoisted. After the Chaplain had delivered the invocation, Commander Chester E. (Blackie) Carroll, USN, read his orders and assumed command. Lieut. J. S. C. (Gabby) Gabbert, USN, the Executive Officer, was ordered to set the watch. Almost immediately a freight car was on the pier and word was passed that was heard all too frequently during the next week, “All hands not on watch lay up on the dock to handle stores (or ammunition).” The ship’s ability to swallow so much was next to miraculous. The least salty sailor was sent to the Officer of the Deck on one occasion and asked permission to use the “bulkhead stretcher” in an effort to get another box or two into some storeroom.

During these days no one mustered at sick call for fear that “Doc” Kelly would find something wrong and send them to the hospital with “Cat Fever.” No one knew what “Cat Fever” was and no one wanted to be accused of fooling around with cats, especially since there were some pretty “doggy” things running around “Beantown.”

The Abbot spent the days of May 10 and 11 on the high seas but made port each night for liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Scuttlebutt said that we would go to Bermuda for shakedown but a few days later found the Abbot in Casco Bay, Maine and there we stayed for six weeks. Five days were spent drilling all hands and exercise firing at towed targets. One of these days the Abbot and the Kidd steamed through the Cape Cod Canal and spent the day training with a tame sub from New London. That night the two ships dropped the hook off Port Jefferson, N.Y., where a “competitive liberty” was held. It was a tough fight, Ma, but…blood spattered blues characterized the next day’s inspection. The days between May 21 and June 17 were spent in and out of Casco Bay. On June 18th, Commander Destroyers Atlantic Fleet came aboard with his staff and held an inspection of the ship, its crew and its ability to properly perform drills. He left with a “Well Done.” The Boston gates, where we all wished to spend the evening, would close in less than three hours so it was full speed ahead. The Abbot made the run in two and one-half hours.

All of the old haunts in Boston were visited again and some of the politicians were able to wrangle a forty-eight or a seventy-two out of the Exec before the third of July when the Abbot once again stood out for Casco Bay. Hardly had the hook been dropped when the ship was ordered to escort the New York to Hampton Roads, Va. Shortly after the first line was over on the dock at Norfolk, the Abbot got underway for New York City. She steamed north with the Block Island, later sunk by enemy action, as far as the entrance to New York Harbor where she was detached to proceed to Casco Bay. The men got a breather in Casco and a liberty or two in Portland, Maine. We steamed out again, this time in company with the Texas which also was left at New York harbor entrance. We went on to Hampton Roads and on June 17 struck out with the Cowpens, Kimberley and the Erben for the blue Caribbean.

“Rum and Co-cacola” Trinidad in the British West Indies was the next stop. It was the first foreign port for many. That night offered authorized liberty in the Port of Spain but thereafter only unauthorized liberties could be made in the city and many took the chance. The Naval Base and camps offered plenty of beer and a good baseball diamond. The “DABBLERS” beat the theretofore unbeaten Davis’ officer’s, chief’s and crew’s softball teams.

For a week the Abbot operated with the Cowpens and Bunker Hill. On July 31 we were called to war. Our orders were to conduct a search for survivors of a German sub. Our search proved futile, however, and amounted to a mere chase that drew only a few menacing flares from a friendly patrol plane. Another week of carrier operations followed and on August 11 the Abbot set out for Hampton Roads. Boston was next and there “Cap’n” Carroll relinquished his command to Commander Marshall E. (Skinny) Dornin, USN, and the first day under the new Skipper saw the Abbot at sea again…this time to check the vibration of the ship at various speeds.

One day five unidentified aircraft approaching at fifty miles sent the ship to general quarters to interrupt the home port routine but before the guns began to bark, the planes were identified as friendly.

On August 16 the ship went into drydock again for new shafts. She was there until September 6. During this period the French Cruiser Le Malin was docked astern and the Abbot crew did much to cement the solidarity of their ally, seeking any occasion which offered a visit to the “Frog’s” ship, especially during the hours when the wine rations were being served. Some of the men were able to “cook up” sufficient emergency to get a short leave.