MY NAVY MEMORIES

George S.K. Rider

Five Degrees From No Return, 1956

This is George Rider’s account of the day Abbot nearly capsized in a hurricane. See also George’s stories about the Saint Patrick’s eve tragedy and a memorable refueling operation.

2/19/2008 — The time — Sometime around 7:30 p.m., — Navy Time, 19:30. The place — 4 Shell Walk, Lonelyville, Fire Island.

The temperature outside was 19 degrees. I had arrived from the mainland on the 10:10 ferry for my mid-winter stay, a combination of inspection tour, writing opportunity and macho get-away. The two-legged and four-leggeds in my family showed no interest in accompanying me.

The ambiance at 4 Shell consisted of wall heaters, portable radiators, water retrieved from my well run-off in buckets and cooking pans, a hallway and stairwell draped off, with blankets to confine the heat to the living room, kitchen and small hallway leading to one of the bedrooms, and canned soups and frozen dinners for the bill of fare. No wonder I had no takers.

I had removed the frozen pizza from the oven. The phone rang. It was my wife Dorothy:

“Dear, You just got a call from Ted Karras. He wants to know if we’re coming to the ship’s reunion in Charleston, South Carolina, in early October. He’s anxious to talk to you. Give him a call. Here’s the number. Call me before you go to bed!”

Ted and I were ship-mates on the Abbot in 1956-1957, an action-packed time in my life. He is retired, living on Cape Cod.

I had put off responding to the letter and forms mailed to me in December. I downed the pizza, reached for the phone and dialed his number.

“Hi, Ted, George Rider here. How the hell are you?”

“Hello, Mr. Rider, I was talking to some of the guys — Cogan, Beavers, and Wilkerson. They want me to make sure you’ll be there.”

My mind began racing backwards, like the spool of a movie projector, in reverse. Suddenly, stop! There I was age 23, standing on the pier at “Ships Landing” in Newport, Rhode Island, with my orders, in my brand new khaki uniform, my suitcase and duffle bag in hand, waiting for the liberty launch to take me to my ship. I well remember the knot in my stomach. I had graduated from Yale in June 1955 and was commissioned as an ensign. This was the first day of my active duty assignment, July 2nd, 1955. The fear of the unknown and what lay ahead, had the butterflies in my stomach fluttering overtime.

“Ted, for God’s sake it’s been 50 years. Please drop the Mr., call me George. We’ll be there. By coincidence our anniversary, 44 years, is October 2nd. Great way to celebrate.”

“Mr. Rider-Er, Er-George, my son-in-law just walked in. Last night I was telling him the story of the hurricane we survived in 1956. I called it “ Five degrees from no return.” He was fascinated by the adventure. Would you mind telling him what you remember?”

Ted handed the phone to his son-in-law.

“Joe, George was my Division Officer way back then.”

“Nice to meet you Joe.”

Joe, have you ever been scared out of your wits? For more than an instant that afternoon, I was. The time was spring 1956. We were scheduled to begin ASW (Anti-Submarine Warfare) exercises in the Atlantic, off Bermuda with a convoy of replenishment ships.

The sea grew angrier as we moved south from Newport. A hurricane had been tracking lazily north, northwest from the Caribbean, changing direction without notice. Not by design, we were heading directly for it. No matter what course we tried, the storm seemed to counter, until we were being pounded.

We were in the middle of it. I was OOD (Officer of the Deck) on the 4 to 8 p.m. watch, (1600-2000 hours). I had relieved Gene McGovern, the operations officer. Next to the Captain, W. W. De Venter, “WWD” to us, he was second-best ship handler aboard. Gene had been on the bridge for 10 straight hours. WWD had moved to his sea cabin, just aft of the bridge, as the sea conditions worsened. He spent most of the time seated in his swivel chair located in the most forward part of the wheel-house where he had an unobstructed view over the bow.

We were operating with seven other destroyers, a squadron consisting of two divisions of four ships each. The squadron commander, with the rank of captain, was located on the lead destroyer. We were arrayed in a line with proper spacing between the eight of us. Movement about the ship was precarious, to say the least.

A Fletcher-class destroyer has a break — an open space — on the main deck amid ship between the superstructures fore and aft; both are linked one level above by an open deck connecting the two superstructures, known as the 01 level. The only protected access from bow to stern was below the main deck. The sea state was so treacherous that WWD ordered the water-tight doors connecting the below deck spaces lugged shut.

Only men in the forward sections of the ship had sheltered access to the bridge. For 20 hours, the men quartered in the after part of the ship, mainly engineers, had no access to the bridge and were relegated to their spaces with no hot food. Movements on the main and 01 decks were out of the question.

Joe, your father-in-law was “boatswain of the watch”, directing the men standing watch: lookouts, helmsman, lee helmsman, quartermasters, radioman, and back-ups, that afternoon. I had the con, the responsibility for running the ship. The captain was either on the bridge or in ear-shot of the activity in his sea cabin. The squadron commander, located on the lead destroyer, gave directions for course and speed. We were third in line, heading straight into the waves. I was braced in the open shell door leading to the starboard wing of the bridge. The ship was climbing mountainous seas and then crashing down to the troughs. We were steering 040° and our speed was 12 knots.

Crackling over the radio came the order, “Change course, come to 130, speed 15 knots.”

I grabbed the mike and acknowledged receipt of the order. I repeated the order to the helmsman and the lee helmsman. “Right full rudder, come to course 130. Make turns for 15 knots.”

The captain was in his sea cabin. He came racing back to the wheelhouse. Ted announced, “The captain is on the bridge.” WWD came bursting through the shell door past me and moved to the outer end of the open starboard wing of the bridge to assess the sea state, just as we were slowly coming to the new heading.

The order never should have been given. We were lumbering into the trough, now parallel between two huge waves. We were thrown over on our side. I lost my grip on the knife-edge of the shell door and hurtled out as the ship rolled steeply to starboard, piling on to the captain who was clinging to the alidade (a navigational device) bolted to the deck on the outer part of the starboard wing of the bridge.

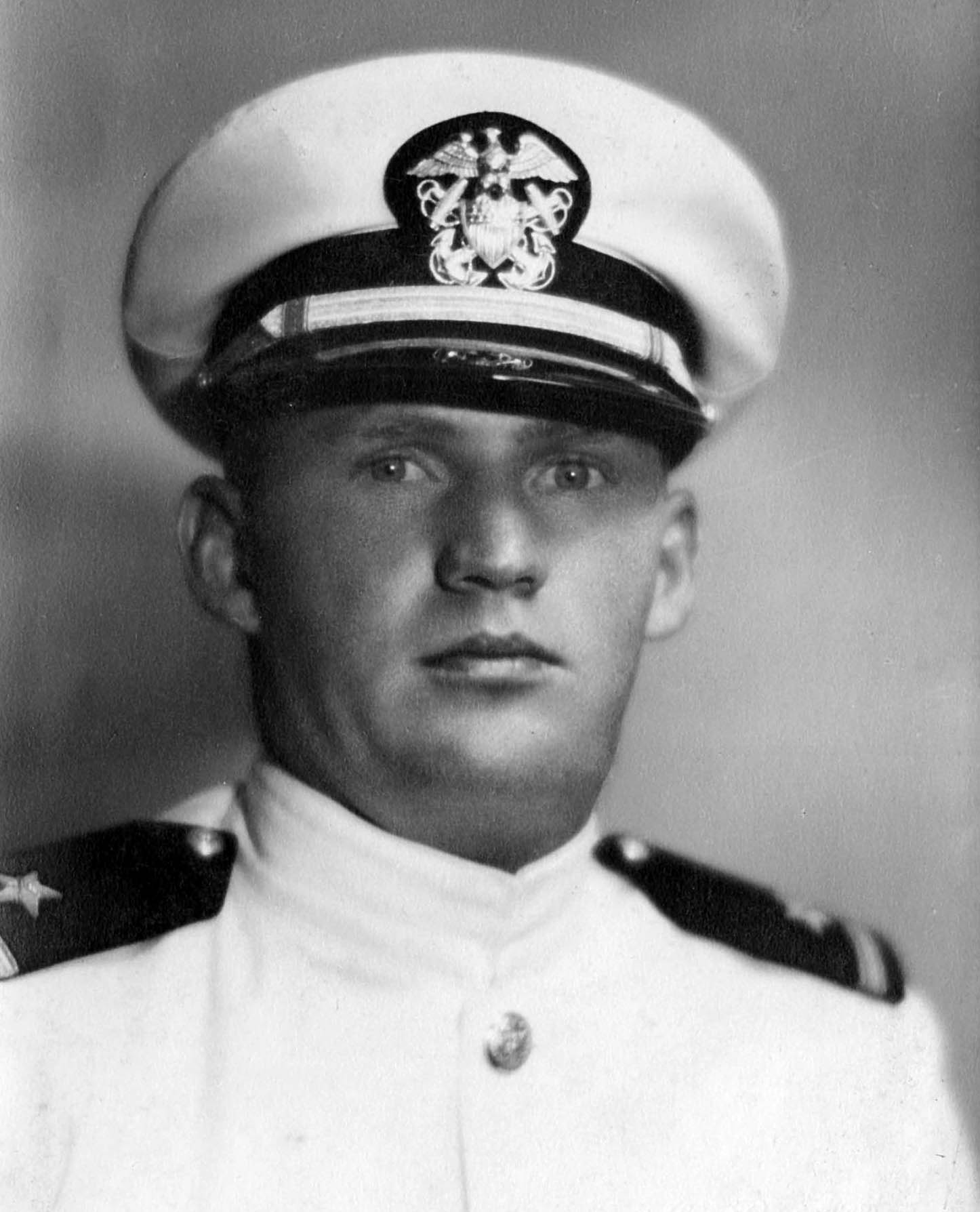

Using a 1944 photo taken at anchor in calm waters, Abbot’s predicament in the 1956 hurricane is clearly visible; once the capsize angle is reached, a ship cannot be righted.

We held on side by side as the ship continued to roll further and further until it seemed like we could reach down and touch the boiling sea reaching up to us. It was angry and black, fizzing like a glass of Guinness first poured. Finally we stopped. The ship shivered and shook. We laid there for what seemed an eternity. Slowly, ever so slowly we began to come back. We had come within 5 degrees of capsizing.

We later learned that we had rolled 63 degrees, “Five Degrees From No Return.” Had we not been properly ballasted, this story might never have been written. A capsizing angle calculation, called the Righting Moment, takes into account the ship’s center of gravity and ballast. At 68 degrees we would have had it!

WWD screamed over the roar of the sea, “I have the con”, relieving me on the spot. As we continued to recover, he inched his way into the wheelhouse and gave orders to return us to a course heading into the waves, at the same time adjusting speed to enable us to maneuver more easily in the treacherous seas.

He grabbed the radio mike communicating the orders from the squadron commander, and bellowed into it “What are you doing? Are you trying to sink us? I’ll take care of my ship. We are steering independently and suggest you do the same until we work out of this.”

Click! He slammed the mike back into its cradle. We resumed our course. The violent motions of the ship were no longer as severe.

“Mr. Rider has the con.”

The engineer on watch was bleeding profusely, blood spurting from a gash on the right side of his neck. Ted and WWD were trying to undo the metal chest-plate fastened around his neck that had been thrust upward when the ship rolled and he was thrown through the shell door. The wire connecting the speaker on the metal plate to the power source had snapped taut causing the cut. They finally freed him and two sailors took him below for repairs, a total of 21 stitches. The gunnery chief broke four ribs when he was thrown against a bulkhead in the chief’s quarters and one of the seamen in my division, off watch, suffered a concussion when he fell and banged his head on a table in the mess hall.

We and the next two destroyers behind us took water down our stacks.

Joe, No one aboard that day will forget that hour and what almost happened. Ted and I had more than a bird’s eye view of the adventure. WWD was never reprimanded for disobeying orders and we all lived to tell the tale. WWD was much loved and admired by the entire crew. His actions that day added to his legacy. He had survived Pearl Harbor, as an ensign taking a destroyer to sea in the midst of the Japanese attack, and he was on the bridge of a battleship Arkansas on D-Day. He told us later that surviving that storm was as memorable as anything that he had experienced in his career.

Joe, Ted mentioned that you might be attending the reunion with him. I hope you do and look forward to meeting you. This and lots of other stories from different eras will be told and retold all day and into the nights long after the wives have packed it in.

I hope you liked what I added to Ted’s story.

— George S.K. Rider