CHAPTER NINE

TOKYO BOUND

Despite the ever tiring task of replenishing ship, the crew found time to knock out those last minute letters and scoff a few more brews at the Osmena Recreation Center. Some of the fellows very profitably capitalized on the Jap invasion currency. Those “boots” on the flat tops and battle wagons had been too busy fighting the war to obtain any of the worthless Jap invasion money, so they were soft touches for our super-salesmen.

July 1 was a very significant day in the history of the Abbot in that it marked the end of our tour of duty in Philippine waters, and the beginning of a campaign that was to be the final one of the war. The coming operation, we hoped, would be the last of our “one more operation” sequence.

The previous evening the Captain’s Gig and crew failed to return to the ship. We signaled every ship which might possibly help us to locate it. Still searching, we were steaming out of the bay when a merchant ship contacted us and informed us that the Dabbler boat crew had taken refuge alongside. The Skipper conned the ship out of column and practically alongside the merchantman, and lost very little time in hoisting the crippled Gig and smiling crew aboard.

Regaining our station in column with DESRON 48 (plus the Heerman) we steamed out of San Pedro Bay in company with Cruiser Division 17. Rear Admiral J. C. Jones, USN, in the Pasadena was O.T.C.

Yes, we were Tokyo bound, and as a part of Admiral “Bull” Halsey’s mighty Third Fleet. The force designation was TF 38 which comprised over one hundred combat vessels under the tactical command of the late Vice Admiral John S. McCain, USN. Needless to say, everyone was deeply impressed with the growth of our United States Navy; and it was quite in contrast with the Philippine Navy to which we had been forcefully attached for the past nine or more months. The complexity of organization and the speed at which maneuvers were conducted were a bit confusing at first, but in short order we had adapted ourselves to the situation and were performing our tasks like the old Pacific veterans that we are.

As we proceeded on the Road to Tokyo there was scarcely any opportunity for rest and relaxation because of the frequent drills which brought forth the familiar cry, “All hands man your battle stations.” Anti-aircraft firing, surface firing, simulated air attacks, day and night torpedo runs, numerous battle practices, disposition changes, and other high speed maneuvers, all designed to whip the force into shape to meet any type of opposition the Japs might offer, took a heavy toll of “rack time” from all hands. Many times during that first week of the approach to battle we wished we were back in the easy-going Philippine Navy.

On the second day out from the Philippines we rescued one of the Monterey’s fighter pilots who had been forced to set ’er down in the drink. He rode the “Dabbler” for a few days, and I think he was glad to get back to base after rolling and pitching on a tin can. The Monterey did pass us the consolation prize of 20 gallons of ice cream for our rescue of her pilot.

Heavy seas were a constant reminder of our fight against such unpleasant elements off Lingayen Gulf. But the weather now as we proceeded north was rather cool, and the John L’s were eagerly donned, especially by topside watchstanders. The swells were breaking over the bow with such force that often the director crews were drenched with icy spray. The sudden change from our tour of tropical duty resulted in a number of colds. But the APC boys kept the crew in fighting condition, and the growing tension as we drew nearer to Nippon Land, left us with little thought of minor discomforts.

On July third we made a rendezvous with the service group assigned to task force 38, and commenced the first of our many underway replenishment and refueling exercises. The “Dabbler” was assigned the duty of passing mail, which by now was an old and monotonous routine job for us. But added to such duties was that of ferrying pilots between the carriers of not only our own group but those of groups one and four. During the course of such duty, we were honored in having Admiral Byrd, of the famous Byrd Expedition, as a passenger.

After completing fueling exercises, the force conducted AA firing practice at radio-controlled drones. Again the “Dabbler” was assigned to special duty, this time retrieving downed drones. However, we did have the opportunity to fire a few rounds, and gun #2 knocked down one drone with as many rounds.

The next day, July 4th, we were assigned to picket duty, taking station some fifty miles from the group and in the direction of Tokyo. Some of our destroyers which were lost at Okinawa, were performing this same hazardous duty when a few of the Kamikazes took their last dive. Naturally, we were a bit on the nervous side when we found ourselves more or less alone. But the absence of enemy contact soon made us relax, and we experienced one more uneventful day. Frankly speaking, a few of the fellows were a bit disappointed.

Nevertheless, we knew that eventually the Slope Heads from the land of the rising sun would find us out and attempt to interrupt scheduled operations, and July 5th brought our first contact with enemy aircraft in the current operation. But for the effectiveness of our combat air patrol two of the Nips would have gotten in to our group (TG 38.3). Enough praise cannot be given the fighter director officers who most efficiently plotted all enemy contacts and kept all commands concerned alert to the immediate as well as distant dangers from the air. The close coordination of all four task groups and their air arms, without doubt, was responsible for keeping our losses to the very minimum of any operation or campaign thus far in our naval warfare.

Floating mines proved a constant menace to our forces, and the Abbot, in sinking her share, fell into another old routine. Though an encounter with a contact mine (or any mine) can be very disastrous to a tin can, our good fortune in mine-infested waters at Corregidor left us rather cocky, nevertheless cautious, of such dangers.

Lack of further enemy contact put us much at ease, yet left us wondering about the Japs. We knew that they could hardly have more than the nucleus of a surface fleet. Too, we knew that their air power was dwindling, but the absence of air contacts led us to believe that Tojo might be saving his best for an expected invasion of his homeland. So it was in this frame of mind on July 10 that we watched the break of dawn and the launching of the initial air strikes on the Japanese home island of Honshu. Because of the necessity of extreme caution and alertness on this occasion, the usual pre-dawn alert was extended throughout the greater part of the day. Consequently, chow amounted to tasty K rations, (our sympathies to the dogfaces and gyrenes), consumed at battle stations.

Contrary to expectations, there were very few air alerts that day, and none of the enemy aircraft got within visual distance of our group. All Nip Airdales who attempted to follow our pilots back to their carrier bases were either spotted by the pilots themselves or picked up by radar and consequently disposed of; or as was heard over the air frequencies, “splash one bogey.”

Two days of air strikes failed to bring action from the enemy in any major sense, though our pilots and plane crews had numerous encounters over and near the targets. Actually, the Japs were caught with their pants down. Either that, or they were reluctant to oppose our forces in any great strength. Stories of our returning pilots would undoubtedly make very interesting reading, but we on the tin cans were denied much of these accounts, classified “military information.” We got the latest dope from stateside news broadcasts as usual.

Following the initial air strikes, the force retired for replenishment of logistics, which event was scheduled to take place about every fourth day throughout the operation. The retirement this time was to the north in order to confuse the Japs as to our exact location. Admiral Halsey, our fleet commander, had openly defied the Japs to come out and fight, but evidently he did not consider it wise to give them a set up.

The weather was not entirely in our favor, though we continued to press home devastating strikes on the Jap home islands. Adverse weather is ever a hazard to carrier operations; and due to various conditions (not detailed herein) a number of our pilots hit the drink and the ever alert DDs proceeded to the rescue. Unfortunately, some of the men were never found.

If the Nips harbored any thought that we had already ventured as near to their back door as we dared, such absurd thinking was clarified when on July 14 Bombardment Group Able, consisting of the battleships South Dakota, Indiana, Massachusetts, the heavy cruisers Chicago and Quincy, Destroyer Squadron 48, less the Kidd, plus the Heerman, set out to shell the coast of northeastern Honshu. Our target was the steel mills at Kamaishi. As we drew near the shore at high speed, tension began to mount. Anything could happen now. Never had we dared risk our surface ships so close to Japanese home soil.

The Dabbler’s position in formation for bombardment placed us broad on the bow of the heavy ship column and on the engaged side of the battle line. Approximately four miles separated us from the shores of Japan when the South Dakota fired the first salvo, giving her the honor of being the first major surface ship to fire on the Japanese home island. Broadsides from the five heavy ships soon brought billows of smoke and flame from the mills, bridges, harbor works and surrounding buildings. It was a very pleasing sight to see. Each reverse of course (always inboard) as we steamed back and forth, brought us nearer to the beach until the Dabbler was within 3,000 yards of the shore on the last pass. Again there was very little opposition, though one of our spotter-fighters was shot down by enemy AA fire.

During the bombardment a surface contact was picked up by radar and DesDiv 96 was sent to investigate. The contact turned out to be a Jap tug and barge which were eliminated with no casualties to our boys.

Even before we had departed from a demolished Kamaishi, Admiral Halsey had announced to the press that U. S. surface units were shelling the Japanese home islands and he specifically named several ships. This was a departure from security procedure in the past, but it further defied the Japs to come out for a showdown fight.

We rejoined our respective carrier groups the following day and retired for replenishment exercises with one service force. Operations extended into the night and the typical American boldness was exercised when the ships were lighted to facilitate the handling of stores.

The week following was spent in striking the Jap home islands from Hokkaido to Kyushu, refueling, replenishing, retrieving downed pilots, sinking mines, passing mail, and numerous other routine operations.

On July 30 we were detached to carry out a bombardment mission on the city of Hamamatsu which is just south of Tokyo. This time our bombardment group had grown to include the heavy cruisers Boston and St. Paul and the DD Southerland, plus the British battleship, King George V, the cruiser Maria and the destroyers Ulysses and Undino. Having had little opposition at Kamaishi, we approached the target with only the normal tensions of war. Approaching any target is always a bit trying on the nervous system, but we were confident of our ability to justly deal with any opposition we might encounter. Unlike Kamaishi, Hamamatsu was hit at night. The heavies were using sixteen inch tracers and to see them arching through the air and then exploded on the target reminded one of a colorful Fourth of July celebration at home.

On July 31 Lt. W. R. Baranger, our executive officer, was detached from the Abbot and transferred to a tanker for transportation and subsequent return to the U.S.A., via air. “Walt,” as he was known in the wardroom (and no less among the crew), had served the Dabbler as executive officer since the early months of ’44, when Lt. Comdr. J. S. C. Gabbert (then Exec) was detached to take command of the USS Bell. Though tentative plans were to return the Abbot (and others) to the States for yard overhaul on or about August 10, it was an envious crew that bade Lt. Baranger farewell and Bon Voyage. But an able officer, Lt. D. E. Lassell, had relieved Lt. Baranger, and the Dabbler was soon settled to the task at hand — hunting Japs.

The month of July had been a prosperous one for Task Force Thirty-Eight. What few ships had been left for the Japs to call a fleet were now resting on the bottom of Nippon harbors throughout the homeland. Airfields and factories had been gutted, other military targets demolished. Enemy air power was at the ebb. In short, the Japs were fast being brought to the realization that it was futile to continue to resist. How much longer would they continue to oppose such overwhelming force?

But the job was not yet complete, and the early days of August found TF38 moving in to tighten the noose around Hirohito’s slender neck.

On the afternoon of August 7 a balloon was sighted low on the water and the Dabbler was sent to investigate same. After cautiously observing a half submerged undercarriage, the Skipper decided to play it safe, and gun #42 expended one round of 40mm ammo in destroying another of Nippon’s weapons of war. Everyone had his own ideas about the balloon, but nothing definite was learned about the mysterious undercarriage. It could have been one intended for the U.S.A.. Whatever its purpose, it will now harm no one.

The next morning at 0500, our squadron and cruiser division 17 were sent to investigate surface targets about 63 miles away. This we thought, might be the Jap fleet. Three hours later and while reorienting at a speed of thirty-two knots, our starboard propeller dropped off. The ship shook violently and immediately swung to starboard as speed was suddenly reduced to fifteen knots. Some few men sleeping aft momentarily feared we had struck an underwater obstruction, possibly a mine. But the truth of the incident was soon ascertained and, upon orders, the Dabbler proceeded to rejoin the carrier group. The weather was quite foggy, and it was with some little difficulty that we limped back into formation with the carriers. The night hunt proved negative, much to the disappointment of all hands.

Unsatisfactory weather necessitated the canceling of air strikes on August 8th. Destroyers low on fuel were refueled from the heavy ships and the force retired to the northeast.

The Dabbler, being a cripple, did not participate in the bombardment on August 9th. With the weather improved, air strikes were launched on Northern Honshu on the 10th. The usual practice of Jap planes attempting to follow our planes back to base resulted in numerous air alerts for our forces. Our pilots shot down most of the intruders before they could make any runs on surface ships, but this day a few Kamikaze boys did penetrate uncomfortably close. The Wasp accounted for one within visual range of our group; another made an attempted run and was turned back by gun fire. Apparently he was not ready to die for the Emperor, though I dare say he never made it back to his own base.

Our destroyers on tomcat duty underwent several air attacks, and the Borie was hit badly when one of the Emperor’s best took his last dive. The Dabbler was ordered to join the Borie, and after receiving the Alabama’s medical officer and three pharmacist’s mates, we proceeded to assist the stricken ship. Plans were to transfer the serious casualties to the Abbot, but it was after dusk and the sea was a bit rough when we went alongside the Borie. Such a transfer would further endanger the lives of the wounded, so upon mutual agreement by the commanding officers the wounded were retained on the Borie, and the Alabama medical officer and assistants, plus our own Lt. Mrazek, Jenkins CPhm, and Van Hoy Phm2c, were transferred to that ship. Van Hoy had to be returned shortly for more blood plasma. Conditions were pretty bad and the Docs really had a rugged time, but the lives of many were saved.

Later that evening we were ordered to rendezvous with the service group where the hospital ship Rescue was believed to be. More medical supplies were transferred to the Borie and at noon on the 10th we joined the service group. But the Rescue was not present. The Lardner was ordered to join our unit (Abbot-Borie) and we immediately proceeded to the northwest where the Rescue was estimated to be. En route the Borie buried her dead and held services for those missing in action.

It was well into the night when the Rescue was sighted, but the Borie immediately went alongside and commenced transfer of her casualties. At the same time we recovered our capable medical staff. The past twenty-four hours had been trying indeed for these men.

Shortly after midnight, the Borie having completed transfer of casualties, we set our course for Saipan Island, Marianas. The presence of a typhoon forming to the south resulted in our being ordered to rejoin the service group. We remained with this group until August 13 when we were ordered to again proceed to Saipan.

In the meantime the Atomic bomb had been loosed on Japan and there were rumors that the war was practically concluded. The Nips had had enough. The order to our forces to cease hostilities came on August 14th and in joyful reverence the Captain talked and prayed with the crew. Good fortune and Almighty God had been good to the U.S.S. Abbot and her crew — and now we were going home.

WAIT! Read these last few words again. Yes, WE ARE GOING HOME! After two long years in the Pacific the Dabbler was being returned to the Promised Land — the good ole U.S.A. True, many of our fighting men had spent longer periods overseas, but we were well deserving of a rest.

We were a happy crew as we steamed into Saipan Harbor. An inspection of our damaged shaft necessitated our going into dry dock, but in the meantime we enjoyed a bit of recreation on the once bloody beaches of Saipan Island. The Chief Engineer, Lt. (jg) Koster, was temporarily detached and sent via air to Pearl Harbor, thence to the U.S. to get things squared away with the yard. Too, he was to arrange transportation for the first leave parties which our congenial Skipper planned to shove off as soon as possible after we arrived on the coast. The navy yard to which we were going was not yet known.

Our eagerness to be on our way made time drag, but on August 22 the Dabbler commenced the second leg of that long road back. The homeward bound pennant had long been eager to climb the mast and stream her colors from the truck; and a more eager crew was waiting for the Captain to give the order “run ’er up.” That he did, and with pennant flying and spirits high, we set our course for Pearl Harbor, T.H.

All hands willingly turned to but, only the necessary ship’s work done in the process. The turning to was in breaking out those long idle dress blues and getting them in shape for those stateside liberties, which proved quite a task. Many men had outgrown. their uniforms; some were too loose fitting; and numerous other problems confronted them. But through the efforts of C. L. Woosley, N. P. Ross and C. A. Richards, officiating as ship’s tailors, the crew was fairly presentable when the Captain held personnel inspection en route to Pearl.

As we entered Pearl Harbor a message from Commander Destroyers Pacific Fleet was received inviting the Abbot’s officers and crew to an open house in celebration of our return from the wars. Most naturally we accepted, though it was impossible for all hands to attend. There was not sufficient time for the Captain to grant liberty in Honolulu, but this time there were no gripes heard from any of the men.

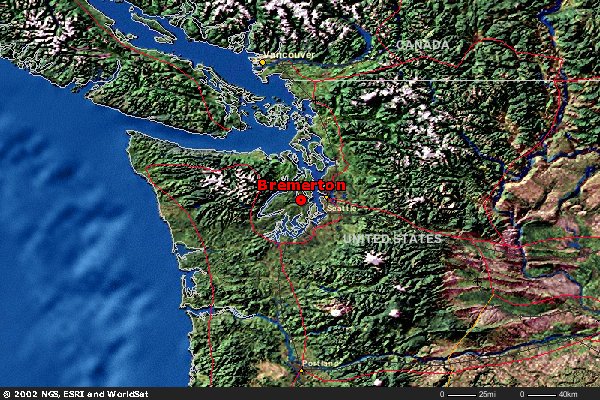

We soon learned that the Abbot had been assigned to Puget Sound Navy Yard in Bremerton, Wash., and the day following our arrival at Pearl (Sept. 1) the Dabbler commenced the last leg of the homeward bound trip. With only one screw, speed was held to 16 knots which seemed, and was, very slow indeed. But the six days between Pearl and home gave all hands an opportunity to make the necessary last minute preparations for the coming tour of “stateside duty.”

September 7 will be considered by many as the most significant day in the history of the Abbot, for on that day we entered Juan De Fuca Strait — home waters. Others will always remember September 8, for on that day two years ago the Abbot left Boston for the great unknown. Whatever the remembrances of individuals, the author of these lines believes that all hands are united in saying, “thank God the war is over, and we are home.”