CHAPTER SEVEN

THE ABBOT AND THE PHILIPPINE NAVY

With the light-headed, bright-eyed appearance of the crew making — it evident that the facilities were not available for an old-fashioned binge, most of us greeted the New Year’s dawn, sober and more rested than any year since we were seven years old. Having offered itself as a theatre, trading post, tavern, repair ship, and as an outlet for the urge to visit, chew the rag, or just whip the dog, the Cape St. Elias took its place among the host of other ships that have mothered us from time to time.

On 2 January we steamed through Surigao Straits, scene of the overwhelming defeat of the Jap fleet a few months before, and started out on the Lingayen Campaign. Over the silt-covered, rusted hulks of the Emperor’s once proud fleet units, slipped one of the mightiest fighting task forces to meet the Nips in that theatre. Composed of a majority of the heavy units salvaged from the Pearl Harbor stab in the back, these ships were soon to find revenge and prove they still had a Sunday punch left.

Knowing our movements in the confined waters were somewhat limited, the Japs took every opportunity to capitalize on it. Our task force was covered with an umbrella of the fly-fly boys from the baby flattops who splashed several of the enemy airborne planes and worked over nearby airfields and air installations.

With oriental stubbornness the “slant eyes” tried, and tried again. Using every play in the book, running around the ends and through the center, they found our pilots were up to all their tricks. On the 4th, toward sunset, one Kamikaze scored a hit on the Ommaney Bay, crashing into her flight deck. In a short time, thick black smoke developed along with heavy explosions and crackle of small arms ammo. Despite all efforts to save her, fires got out of control and the stricken carrier had to be sunk. The destroyers assigned to the task turned-to with a will, braving the dangers, thinking only of helping to save as many lives as possible. The Bell, commanded by Commander Gabbert, our former Exec, was one of the destroyers which attempted to fight the fires and pick up survivors that had abandoned ship. Just at dusk the Task Group Commander ordered the Burns to torpedo the Ommaney Bay which by this time was a flaming wreckage, far beyond salvage.

The next day it was like Macy’s basement, with our task group for the bargain. The Kamikaze boys dropped in all over the place, scoring some hits, but we plowed on knowing that our turn to dish it out would come soon.

“Time” made mention of a hundred-plane raid, but thanks to our CAP, we didn’t see quite that many. Typical of the action were three callers who, after being guided by the Divine One himself, got within sighting distance of the formation. Being in the 2% by which Admiral Mitcher is annoyed, they hit the screen with the idea of paying their respects to the captain of a carrier. The Maury, an old timer at this sort of gate crashing, punched two of their tickets before they got close, nipping the third one as he turned back on the poor, almost defenseless “can” — to argue no doubt. This was the last real trouble our group was to run into with the Nips during this campaign.

The China Sea in itself is a miserable, rough, white-capped body of water but when mixed with the proper amount of beans, rice and tomatoes, it becomes a lasting, unpleasant memory. No one could do this period justice. “Meat” was plentiful, raisins never trusted, K rations a treat and the storerooms were more nearly emptied than ever before. It affected each man in a different way although some little discomfort was experienced by everyone. It is safe to say that beans were never received as enthusiastically. Not having too much to do, the Supply Department fell out of its normal orderly routine and ended up with new duties.

Mort, the Pirate, was assigned the difficult job of figuring out the number of combinations that could be made from types of food supplies on board — all three of them. Perrin’s job was to transpose Mort’s combinations into chow, and thence to the mess hall. Disposal of all but a small part of this “combination” was under the supervision of a mess cook and he worked like heck carrying it all back. “Dutch” lorded it over the can openers, accounting for every can, as one couldn’t leave anything in the bottoms or on the sides, and their potential use as weapons against the “S” men was not overlooked. Two cooks were assigned temporary duty with the bakers to assist them in carrying down the rolls and buns. Floyd had meanwhile dislocated his shoulder taking a very small pan of fluffy, flavor-laden parker house rolls out of the oven. Bonnett, not to be trusted in the storerooms with the chow, was given the unpopular job of giving a nightly account of the wonderful chow that could be ours by passing through the hatch on the port side. With Mort so busy on food figures, Jim Crowe had to give his money away nightly in the mess hall so that the crew wouldn’t holler on pay day — he did a commendable job of it too. The rest of that unmentionable group of bellyrobbers acted as bodyguards for the higher-ups, as checkers on break outs and three men won their “E’s” as exterminators! Gad, what a month!

In the meantime our forces were covering the landings at Lingayen Gulf at the same place the Nips got ashore in 1942 and also later landings at San Fernando and Nasugbu. With nothing handy enough to bring the groceries out, the Great White Fathers at Leyte were thoughtful enough to send us a little mail and it did help. This never-to-be-forgotten month came to a close with the O’Bannon, Moore, Goss and Bell chasing down a sub. Later it was learned that these ships inflicted probable damage to it.

That same night we stepped in with some fast company in the form of a cruiser group. We were to stay with them for some time, receive fine treatment, and feel a little reluctant to leave them. Among our publicized companions were the Boise, of Guadalcanal fame, O’Bannon (Little Helena) Nicholas (a loose rail on the Tokyo Express), Fletcher and Radford, of Kula Gulf fame, along with the Jenkins, La Vallette and Taylor, all in and out of the slot so long that they felt like street car tokens. A fine group, all eager beavers and loaded for bear.

The first week of February found us at Mindoro, for a well-earned rest. Our ration books weren’t good for a few more days and we struggled along on what we could grab from other ships. The boys, with their visits to San Jose, undoubtedly carried away a lot of new souvenirs and the more fortunate ones witnessed their first cock fight. With no urging, the lads turned to on the chow when it did arrive. We were all shipshape on 9 February to shove off for Subic Bay.

We looked forward very keenly to arriving at Subic Bay. With Grande Island blocking the opening to the bulging land-locked bay, we were forced to slip in close to the shore in order to pass into the harbor. Quite a treat, being so close to such a fine piece of good earth as that particular spot — after all those odorless atolls — the grassy smell that wafed over us, made a lot of staunch reserves out of borderline cases.

This area had recently been overrun by troops of the 11th Airborne Division, and fighting was still going on back in the hills when we arrived. Because of this, liberty was curtailed and the men — interested in recreation at no matter what the trouble — readily agreed to the executive officer’s suggestion that we take up “fishing.” They were easily discouraged though, and frequent trips were made back to the ship — men mumbled to themselves about not catching anything and left the boat — their place to be taken by someone whose thirst for the sport had not yet been quenched.

The battle of “Zig-Zag Pass” was being fought in the hills just beyond the anchorage, and we could see the columns of smoke and dust rising from both sides of the valley. Gun flashes, fires, tracers and rumblings in the night provided openings for conversation while the daytime exhibitions in dive bombing and straffing afforded a welcome break in our usual in-port routine.

After combat troops had combed the island for possible snipers, we were allowed to visit Grande Island, at the mouth of the bay. American forces were forced to abandon this place in the Bataan retreat and had carefully put all the guns beyond immediate repair before they left. The Nips, confident that we would never return, had gone to no trouble to fix them, and for this reason our entry into the bay was uncontested.

The island, while small, had some interesting points. The arrangement of the guns, the machinery for handling the large calibre ammunition, the dark, damp ammunition storerooms under layers, and layers of thick concrete, the system of observation towers, and the commanding view from the fort of both sides of the bay, were all interesting enough to merit an afternoon liberty.

With so much activity going on all about us, we were rather anxious to get in on the clean-up before Doug had all the Japs run out. Our forces that previously had landed at Lingayen had fought their way down the Luzon valley to the outskirts of Manila, and nightly we could see the glow in the sky, where the Nips were putting the torch to the “Pearl of the Orient.”

With our wish seemingly their command, it was not long before our force of cruisers and destroyers pulled up in front of the Manila Bay entrance on February 13 and sent in some 5- and 6-inch calling cards. The Japs were given fair warning that the lease was up, and that we had intentions of evicting them. So began the initial phase of a pounding that was to last on and off for the next four days. The Japs gave up responding a few days before that. It was hardly profitable for them. With every salvo from the islands or the Rock, the location of one of their batteries was given away and brought a smothering hail of fire from our ships that usually silenced it for good. Even Corregidor couldn’t stand that very long — and the returning salvos became less frequent — soon to be stopped completely.

The entrance to Manila Bay, according to old-fashioned pre-war standards, was an ideal position for defense. Formed by the Bataan and the Cavite Peninsula, the opening to the bay was studded with Corregidor, Caballo Island, El Fraile Island and Carabao Island. Theoretically this was a well fortified area, but the Japs had again unsuspectingly slacked off and failed to rearm the damaged fortresses too well. The bombardment, well planned affair that it was, left the Cavite Peninsula alone — nothing there to bother with. The next link in the fortification was a fort located on Carabao Island which the Abbot personally took under fire the first day, the 13th of February, and gave us no trouble from that day on. El Fraile, standing apart from the others in the southern approach, was a more familiar landmark to some of us. Ripley had at one time or another given it a boost in his “Believe It or Not” column, as the concrete battleship that never moves. The reason — Fort Drum, constructed there by the Americans, had two 14-inch guns in turret arrangement, and a 6-inch secondary battery casemated in the sides in keeping with pre-war capital ship practice. This island received only a few salvos, more to keep the sightseers down, the guns having been effectively put out of commission by aircraft.

Caballo Island, the next nut to crack, standing side by side with the thin end of Corregidor with its seaward side protected by a huge towering white cliff, was an excellent spot for covering the opening to the bay, and the Americans also had a fort there prior to 1942. Opposition from the Nips there amounted to small calibre fire which came from the sheltered side of the island. Because of our location, counter battery firing was difficult.

A few days later, and prior to amphibious and paratroop landings, the Japs started to shoot at our mine sweepers engaged in clearing the area. But our CL’s and DD’s took those shore batteries under fire and silenced them. For sport, the 40mm’s with uncanny precision pried into all the possible eaves on the cliff’s face, making it rather tough for the Japs to use them as observation posts.

The last and most important part of the defense point was the turtle back, tadpole-shaped island of Corregidor. It was there so many real American heroes had died, and for this reason alone our presence there seemed quite important. This was definitely an honorable and important assignment, and our Task Group did itself justice. The initial bombardment with precision shooting in knocking out enemy guns and call-fire in support of the Army were sights at which to marvel.

On February 14th we repeated the performance of the day before, also a little notice to the other islands that we hadn’t. forgotten them, then standing by Corregidor the rest of the day, shooting at targets of opportunity. The minesweeps, doing a superb job for the previous two days, were going into Marviles Harbor, to clean it up for the invasion scheduled the next day. Standing by for counter-battery fire was the La Vallette and the Radford. About 1700 the La Vallette struck a mine. The “Dabbler” was assigned to assist her, and we proceeded at once to approach the entrance to the bay. The Radford, going to aid the stricken ship was itself damaged by another mine. Upon our arrival at the scene, both ships were maneuvering under their own power, and were able to retire. Our medical party, Doc, Jenks, and Mack, were transferred to the Radford to help with the casualties, and we escorted her into Subic Bay.

On station on February 15th, we spent most of the day standing by for counter-battery fire on Corregidor, while the bulk of our formation laid down a curtain of fire for the successful assault landing at Bataan. The only ship damaged was an LSM which sunk after striking a mine before the landing.

The 16th will go down as another “never to be forgotten day” for all men with battle stations topside. We had seats on the 50-yard line for one of the greatest shows we ever had a chance to witness. Army and Navy took turns carrying the ball, both on the same side for this big event — the home team took an awful beating, retreating to the showers, or other spots deep in the earth, soon after the game started.

From the very crack of dawn the ships, high level bombers, fighters, and dive bombers kept a steady rain of shells and bombs falling on Corregidor. The entire island was lost in clouds of smoke and dust for minutes at a time. So close were we that the fall of all the bombs could be followed by eye, and our shirts were stuck against us from the concussions of the larger explosions. The Army Air Force made a review of it. Every type took their turns, high level heavies, parachute bombing by the mediums, dive bombers, fighters strafing — why even a cruiser observation plane requested permission to drop his two little bombs, and went in for a strafing run. Just before “H” hour, the inferno increased, the ships stepped up their fire, each with a certain area to rake over. The entire northern end of the island was covered with explosions, smoke, fire bombs sending their distinguishable black plumes of smoke up among the browner dust clouds.

The entire sky to the eastward was filled with planes, transports carrying the men who were to make the assault landings. They came in very low, seeming to move unearthly slow when compared to the buzzing fighters that protected them. Appearing to just clear the “topside” of the Rock by a few hundred feet, the lead plane disgorged the first nine men of this great aerial invasion — the second such landing to be attempted in the Pacific area. Floating down on the Jap held positions, they seemed so all alone — so insignificant a threat to that huge rock, but seconds later the second nine and soon the third were in the air, a few more minutes found the entire sky filled with troopers on the way down, landing close together. Through the glasses we could see them forming up and commencing to advance on the shambles that were once barracks and a town. The later planes sent food, ammunition, medical supplies, guns and everything else to make this operation a success. Each type of material had an identifying color, and scuttlebutt has it that blue chutes were CB’s being landed to build an officers’ club. Gad, but there were lots of blue chutes!

Hour after hour this steady stream of planes approached the island, dropped their cargo and went their way. While the airborne troops were still landing, the minesweeps once more were on the spot. The waters east of Corregidor and Caballo were to be swept at this time, and with the first sweeps entering these waters the heretofore hidden Jap guns on Caballo Island started firing at the minesweepers. Several ships the “Dabbler” covered the island with rapid fire — throwing up a blinding cloud of smoke and dust — and a killing hail of steel fragment. The minesweeping operations continued unhampered, as the enemy fire ceased in very short order.

At approximately 11:15 the amphibious landing was made at the narrow neck of Corregidor, near the base of Malinda Hill without casualty to any naval vessels. This force, comprised of soldiers who had the day before landed on the Bataan Peninsula, joined with the paratroopers, and before the day was out had driven all the Japs deep into the caves on the northern end, and forced them down toward the tail-end of the island.

Having worked their way well into the inner reaches of the entrance, the sweeps were getting more mines cut than they could handle themselves. Because of danger to the heavier ships from floating mines, the Abbot, Saufley and Hopewell were assigned to aid the AM’s. When the area assigned to us was cleared, we had accounted for six mines ourself, tagging them with 40mm. fire, and had a too close call with a mislaid bomb from one of our own dive bombers.

Standing-by, the night of the 16th, with the Claxton, as fire support ship, the “A” kept up illumination whenever called for by the paratroopers on the island. During the night, after an urgent call from the beach, we sent in a few vigorous salvos, later to find that we had broken up a Banzai attack. We took our congratulations from the beach like veterans.

February 17th found us with new duties when after receiving word to investigate some objects in the water close to the island, we found the first one to be a Jap. Clinging to a board, with a water-logged boat nearby, he was attempting to shoot himself in the head with his pistol. A well directed shot from the captain’s gun distracted him, and as we came alongside, he made one last attempt to drown himself. Now this is a very complicated process and most of the crew never having such a close-up view of such a procedure before we were all very interested in him. A strong line convinced him that life was still sweeter than the other extreme, and we heaved him aboard.

The second object was 100% more interesting, being two Japs, who waved at us, showing a great desire to come aboard and make friends. One was holding on to a long sword and warning was given the men on the lower deck to watch out for it. That was the only thing that prevented it from ending up on the wardroom bulkhead — the Jap could understand English. He immediately tossed it away to show his good intentions.

Having been educated in California this boy was on to the routine we have for prisoners — and convinced a few of his companions to take a chance with him. A member of the naval artillery unit on Corregidor, he had originally intended to swim to Bataan with his comrade, but after trying for two days they had given up all hope of making it. When questioned by the Intelligence Officer of a larger ship, this prisoner gave a great deal of information on the conditions on the islands, the way he felt about the bombardment, the number of men on the harbor islands, and the surrounding peninsulas.

A few fire support missions from the waters north of Corregidor that had been rather hurriedly swept the previous afternoon to the tune of hidden Jap guns completed our work for this operation. The gunners did their usual superb job on these shoots.

Back to the almost pleasant Subic Bay for a little rest and recreation, movies on the forecastle, beer on the beach, and with a legit excuse, a trip to Olongapo. February 21st was Christmas on the Abbot. All the Christmas cards, packages and “wish you were home” notes arrived in 65 separate gooey packages. When dumped on the fantail it made a great pastime. Digging out the smashed cartons and bundles — finding that Aunt Minnie did send you something — but it wasn’t a tie this year — no tie ever smelt like that.

Left Subic Bay for Mangarin Bay, Mindoro, on the 24th of February, leaving the latter port on the 27th for the invasion of Puerta Princesa, Palawan Island. This is the long finger-like island on the southwestern side of the Philippines. There hadn’t been too much Japanese activity there during the occupation, an occasional use of the one or two harbors for fueling stops on their long commercial routes to the rich Indies. As we expected — there wasn’t much opposition to the landing at 0745 on the 28th, and not being in the bombardment group, but standing by for counter-battery fire, we didn’t get to shoot at all. Afternoon brought promise of a little skirmish, with us being assigned to cover two landing craft investigating Turtle Bay a short way down the coast. The landing craft cautiously approached the narrow opening to the bay — sounding as they went, but the search was carried out without incident. Returned to Puerta Princessa at 1530 in time to start for Mindoro with the cruiser group. This operation, quiet as it was, left Doug MacArthur entrenched in the entire length of the Western Philippines from Luzon to Palawan leaving the remaining Japs on the island of Mindanao, last Jap-held large island in the group, to await its fate.

The return trip was routine except for a quick stop at Mangarin Bay, Mindoro. Proceeding ahead of the formation at 28 knots, we entered the anchorage, made a “four bells and a jingle landing” alongside the SOPA for some mail for the group and a passenger, rejoining as they came abreast the harbor entrance. We proceeded on to Subic Bay, arriving at 1800 on March 1st.

With our destination Mangarin Bay, Mindoro, as usual, we got underway on March 4th in company with three destroyers and the Boise and Phoenix. A short stay in Mangarin Bay, and on the 7th we left for our newest liberating operation. It appeared that if any destroyer had earned the Philippine Liberation Ribbon we would certainly be among those considered. The crew figured roughly that we liberated more Filippinos than any other two cans west of the Panama Canal.

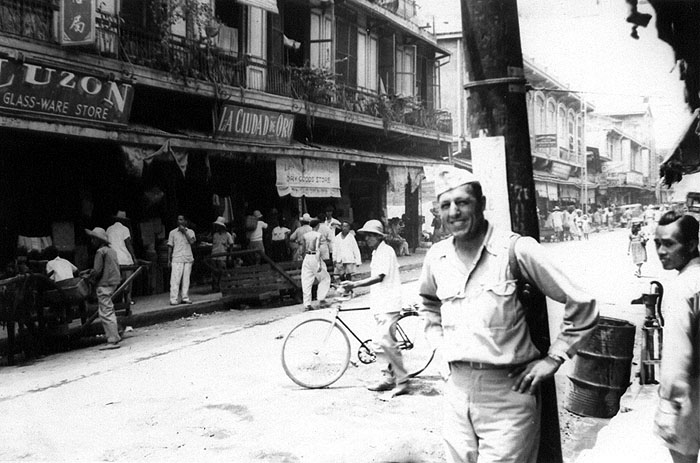

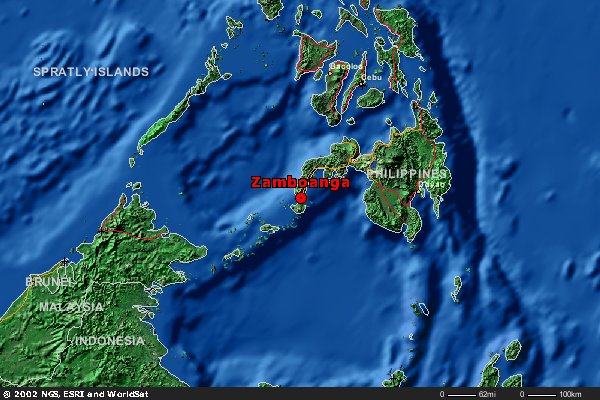

The chosen spot was Zamboanga, third largest city in the islands and site of the former Army Southern Headquarters, located on Mindanao Island. This was the last enemy stronghold in the Southern Philippines — mines were expected and there was as a chance they might have some aircraft saved in the south for just such an occasion as this.

We entered Basilan Straits, between the Zamboanga Peninsula and Basilan Island, on the 8th. Breaking up into two bombardment groups, each with a cruiser and two destroyers, the ships went about their scheduled bombardment without further delay. The response from the beach was so negligible — the place had been terribly over-rated — we knocked off early in the afternoon and just sat around taking in the sights.

March 9th the Abbot added some new experiences to her long list of oddities. We had to dispatch one of our boats to tow the Boise’s plane back to her ship — the pilot having embarrassingly run out of gas — his mission however was successfully completed. Our lookout spotted a plane hidden among the brush just off the airfield, and we had our first “sitting duck” to shoot at. At 1827 a pillbox on Galivan point opened up — and we took it under fire with 43 rounds of ammo, destroying the pillbox and leaving the area burning. We continued to bombard the landing beaches with 5-inch and 40mm fire in preparation for the scheduled landings on the 10th until time to retire for the night.

Units of the 41st Infantry Division made the assault landing at 0900, after the ships of our group and the supporting landing craft, rocket LCI’s and planes had raked the beaches with fire since 0650. The soldiers proceeded to fan out swiftly along the beach, and we moved along with them as fire support ship to the outskirts of the town of Zamboanga. Destroyed several enemy field pieces under the direction of the shore fire control party, but had to retire for the night, before we could locate the position of an enemy mortar that was dropping them in our lines.

Had our own little day on the 11th, being assigned to take the town of Isabella, on Basilan Island, under fire. We loaded ammunition from an LST off Zamboanga and proceeded on the mission assigned. The enemy was suspected of hiding barges in the vicinity. With the aid of the Boise’s spotting plane, we peppered all the likely coves and inlets the pilot spotted us on several barges which were destroyed. With a few parting shots at the town to discourage the Nips from being too comfortable, we retired from the area, apparently chased away by a brave bum boat that had come the longest way out you ever saw.

The Army had the situation well under control on March 12th, and after standing by most of the day, we were off for Mindoro at 1600, making the usual short stop on the 13th of March, thence to Subic Bay, arriving on the l4th.

Subic Bay by now had grown from the beautiful blue bay we first knew, to a crowded bustling harbor full of ships of all sorts. Quite evident were the usual MTB (Mooching Torpedo Boats ), coming alongside for water, to tell us sea stories, take a shower, and leave with half chow. We loved them all — and for once they came through with a suggestion that wouldn’t cost us. Patrolling up and down the Bataan coast, they had a boat a day going into Manila and they offered to take seven of the boys along for the ride. What a scramble for that liberty. Of the lucky winners, “Dutch,” the cook, didn’t like the Manila chow; Lincoln got his signals mixed up and lost his way; Moore and Shaw became hopelessly confused with a truck, not arriving on station until the next day — but they all swear that they had a good time.

The Hobart, an Australian light cruiser taken out of the war with a torpedo in the early part of the Solomons campaign, had returned to the fight once more, joining our group at Subic. She was the new addition as we left for Cebu City on March 24th. The operating area being limited — a portion of our group was left at Mindoro, and we proceeded on with the Phoenix and Hobart up through Bohol Strait — following the path that Magellan’s adventurers had used a few hundred years before on their way to Mactan Island, a few miles beyond our present destination. While this operation was short, it proved to be the most concentrated bombardment that we had ever participated in. In less than an hour our blistered guns had sizzled 705 rounds of 5-inch ammunition into Talisay, scene of the landing of units of the Americal Division at 0828 on March 26th. The remainder of the day was spent in screening the heavy units standing by for fire support, but the land forces met no stiff resistance and they needed no additional help. Casualties were reported to be rather high, the landing beaches having been heavily mined by the Japs. A little excitement was in the offing in the other group, closer to Cebu City. A midget Jap submarine surfaced in the middle of a group of landing craft escorted by destroyers. The ships were in each others line of fire, but, an LCI commander rammed the sub, and she sank out of sight.

We were detached the evening of the 26th, and proceeded to herd a group of LCI’s and LSM’s back to Leyte Gulf. Arrived at San Pedro Bay, on the morning of the 28th, delivered our little charges, and reported to Tolosa, to Commander Philippine Sea Frontier for duty. His magic touch — a few weeks duty with this outfit — and those orders for the states usually came through. The crew was in high hopes for a few hours — until we were sent to the tender for an overhaul period — the fixing up fixed us out here for a few more months.